"A quiet brilliance of the book lies in how Ajarn David reframes customs foreigners often misjudge. He does not defend Thailand sentimentally; he clarifies it."

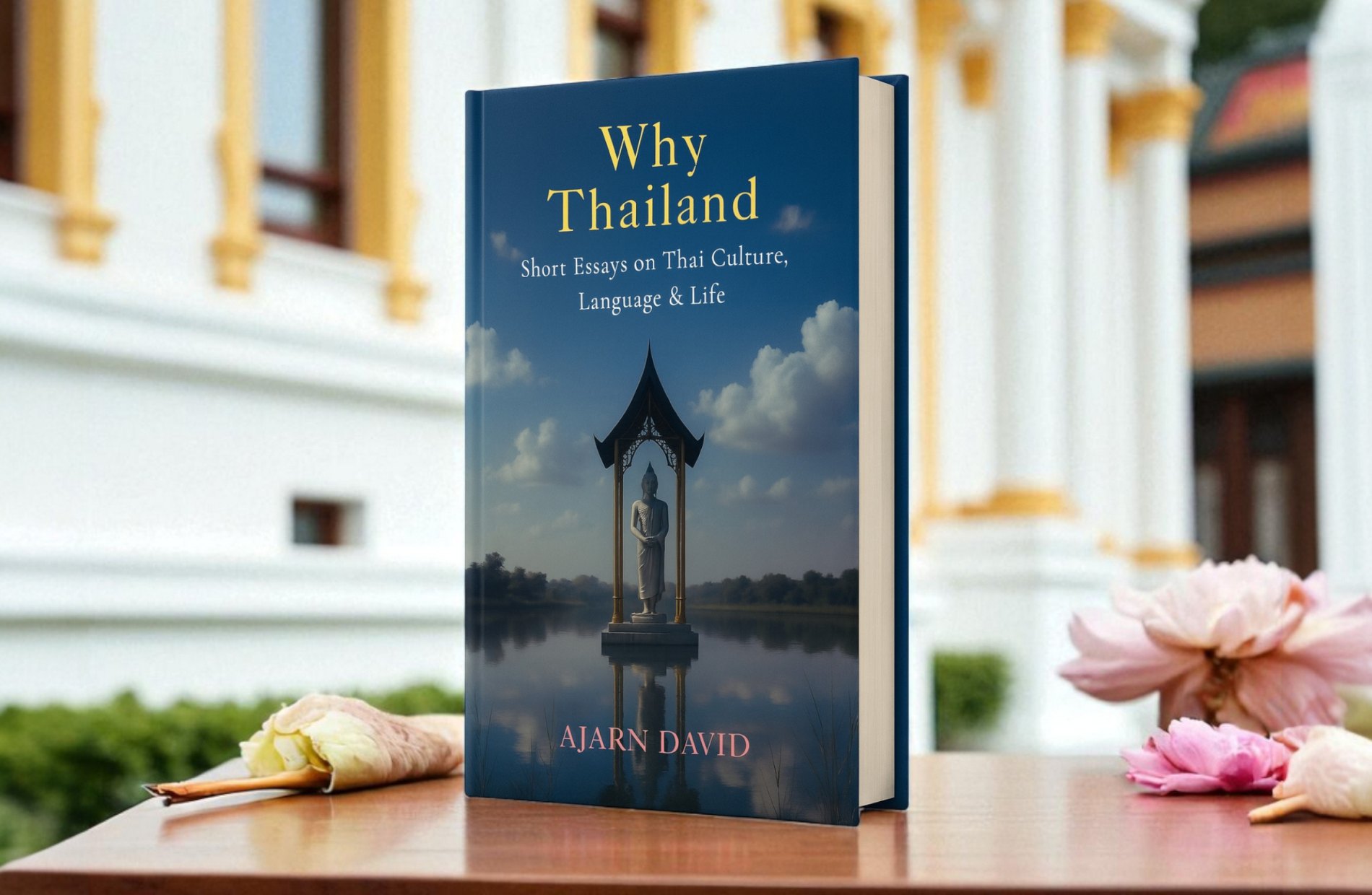

No Ordinary Thai Guidebook

W

hy Thailand: Short Essays on Thai Culture, Language, and Life by Ajarn David accomplishes something no guidebook, travelogue, academic study, or expat memoir has ever achieved in one volume: it bridges three worlds that almost never meet gracefully — the empathetic, the practical, and the Thai.

Most Western writing on Thailand falls into one of three familiar traps: the tourist guidebook, which lists where to go but not why it matters; the academic monograph, which dissects culture from a scholarly distance; or the expat memoir, which romanticizes life through the foreign observer.

Why Thailand does none of these. It listens first. It lets Thai culture speak in its own rhythm — in the pulse of jai yen (cool heart), greng jai (considerate restraint), and mai bpen rai (gracious acceptance) — and then translates those rhythms into language as lucid as it is compassionate, as worldly as it is wise.

A Thailand Seen from the Inside Out

H

aving lived and taught at Thai universities for more than two decades — not in Bangkok’s expat enclaves but in the rural Northeast — Ajarn David writes not as a guest but as someone adopted by the Kingdom.

His voice is affectionate yet analytical, grounded in years of classroom dialogue and temple conversation. This is a man who has offered a wai to monks at dawn, listened to ghost-healers in Isaan, and helped Thai students find their English voice without losing their Thai heart.

Through that lived intimacy, the essays balance ethnography and empathy. Each chapter explores a facet of Thai life — saving face, merit-making, linguistic politeness, spiritual etiquette — revealing how these form a coherent moral ecology.

Like William Warren before him, Ajarn David makes Thailand intelligible to outsiders, but unlike anyone before him, he makes it emotionally legible.

Decoding Thailand’s Misunderstood Traditions

A

quiet brilliance of the book lies in how it reframes customs foreigners often misjudge. It does not defend Thailand sentimentally; it clarifies it.

Take prostration before elders and monks. To the Western eye it may suggest submission; here it becomes a graceful vocabulary of gratitude — a gesture that keeps ego in check while protecting dignity on both sides.

The sin sod (Thai bride “price”) is re-explained not as commerce but as ceremony — a public expression of thanks to the family who raised one’s bride, honoring love’s unseen labor.

Thai time, frequently derided as lateness, is revealed as relational priority — a social calculus that values harmony over the tyranny of the clock. And what outsiders call criticism avoidance emerges as skillful conflict management in a face-saving culture: progress by modeling rather than public shaming.

Throughout the book, Ajarn David similarly illuminates the meanings behind wai, nam jai (water-hearted generosity), and mai bpen rai (never mind). Each custom, once caricatured as passivity or superstition, becomes intelligible as an ethics of compassion and equilibrium.

The result is not a claim that Thailand is flawless, but a demonstration that its most debated traditions make moral sense once you learn the language of the heart.

The Empathetic, the Practical, and the Visionary

E mpathetic, because its essays are deeply human and attentive to feeling. Chapters like “The Way of Thai Listening” and “Understanding Jai” read as quiet meditations: monks walking barefoot at dawn, the ritual of the wai, the art of remaining calm in a noisy world.

Practical, because it serves as a manual for living well in Thai society. Essays such as “The Art of Being Greng Jai” or “Saving Face” explain social codes that no relocation handbook has managed with such clarity. Westerners who wonder why directness can wound, or why confrontation rarely works, will find here the behavioral wisdom that prevents a hundred cultural missteps.

And visionary, because its final section addresses educators and policy-makers. It shows how bilingual education, soft power, and the sufficiency-economy philosophy can guide Thailand’s future without betraying its traditions. The same author who writes tenderly of a forest monk can also discuss curriculum reform and cultural sustainability with rigor. Thailand appears not as a destination but as a living civilization still evolving through kindness, language, and restraint.

Beyond the Farang Gaze

A

For decades, Western depictions of Thailand have been filtered through the farang gaze — outsiders commenting on Thais rather than conversing with them.

Ajarn David dismantles that imbalance by letting Thai terms and moral intuitions lead the discussion. Words like jai yen, nam jai, khwan, and katha are not exotic curiosities but conceptual keys that unlock a worldview where heart, mind, and spirit are one.

He writes English that feels Thai. That is revolutionary. It places his book beside the great cross-cultural classics — Lafcadio Hearn’s Japan: An Attempt at Interpretation, Pico Iyer’s The Global Soul — yet it is more grounded, more emotionally bilingual, more inclusive in spirit. No other work in English has rendered the Thai moral imagination with such intimacy and respect.

A New Model for Cultural Writing

T

he essays, though short, form a grand architecture of understanding. They move from the personal (“Why Thailand?”) to the philosophical (“Understanding Jai”) to the societal (“A Culture of Respect”) and finally to the national (“Cultural Soft Power”).

Each refracts the others, revealing Thailand not as a mystery to decode but as a wisdom tradition to learn from.

Stylistically, the prose is clear yet meditative, blending travel observation with Buddhist calm. Ajarn David avoids the colonial impulse to explain Thailand; he feels it. Readers finish each essay not only informed but centered — as if they’ve spent an afternoon beneath a temple tree with a teacher whose authority arises from stillness.

The Book Thailand Itself Might Have Written

W

hy Thailand may be the only major English-language book that could plausibly have been written by Thailand itself. Every page breathes the nation’s values — balance, humility, sensitivity, grace.

Even the transliteration of Thai words is handled with cultural sensitivity rather than pedantic rules, mirroring the flexibility of Thai life: orderly when necessary, fluid when wise.

Ajarn David also restores dignity to Isaan, the Northeastern heartland too often dismissed as provincial. Through portraits of monks like Luang Pu Fan Acharo and landscapes like Sakon Nakhon, he reveals that the Kingdom’s spiritual capital lies far from Bangkok’s skyline. It is a re-centering few writers, Thai or Western, have dared attempt.

A Thailand Guidebook for the Soul

F

or tourists, Why Thailand becomes the most meaningful guidebook imaginable — one that teaches not what to see, but how to see.

For expatriates and retirees, it is a manual for emotional adaptation — how to live in harmony with a culture that prizes peace over pride.

For educators and policy thinkers, it shows how cultural literacy can modernize a nation without erasing its soul.

And for Thais themselves, it offers the rare joy of seeing their own virtues reflected with accuracy and admiration in English prose.

That universality — appealing simultaneously to travelers, teachers, and Thai readers — explains why this book feels canonical. It does not entertain so much as enlighten, gently. It suggests that the future of cross-cultural understanding depends not on louder opinions, but on quieter hearts.